About

Karst in the Ozarks

Educational resources about our caves, springs, and underground water

KarstintheOzarks.org is a project of the Ozarks Resource Center

The Ozarks are known for scenic float streams and magnificent springs. Where does the spring water come from? How did these big springs form? The waters' travel underground seems mysterious, but it’s actually been well studied and understood.

Ancient forces carved the Ozarks

Water has been carving a rolling, dissected, stream-rich region ever since uplifting deep under the Earth’s crust pushed up the Ozark dome eons ago. Our hills are remnants of the high points of that dome, and our clear streams run through gullies gouged out by the roaring waters of ancient floods, a process continuing today.

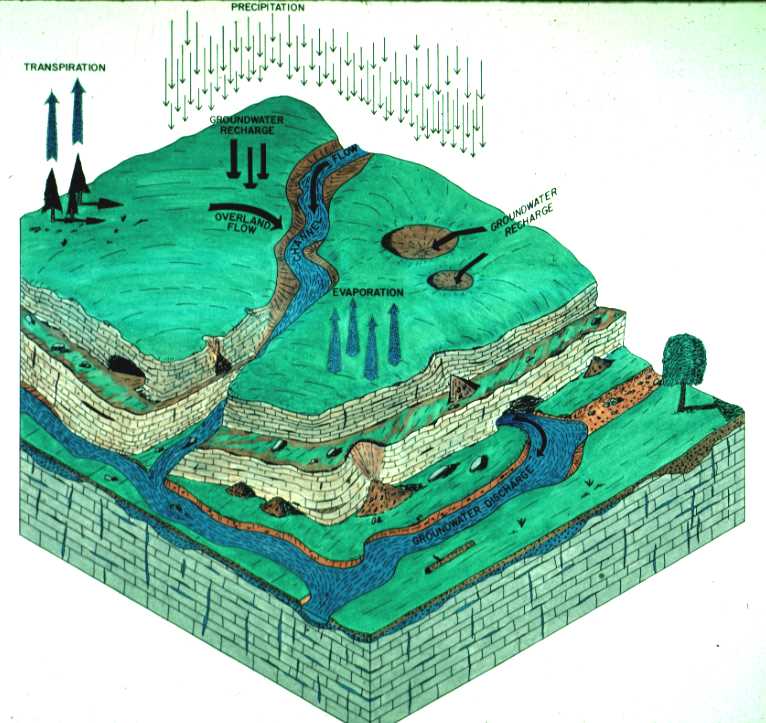

But this carving process goes on below ground, too, because rainwater trickles through our thin topsoil into fractured layers of rock, dissolving it bit by bit to form tiny channels. Over time, these eventually become tunnels that turn into caves. The groundwater running through them emerges as a spring. Sometimes a small part of a cave roof subsides, creating a sinkhole that gives entrance to that cave, or in some cases a cave roof collapse reveals a stream that previously flowed underground.

From rain to stream

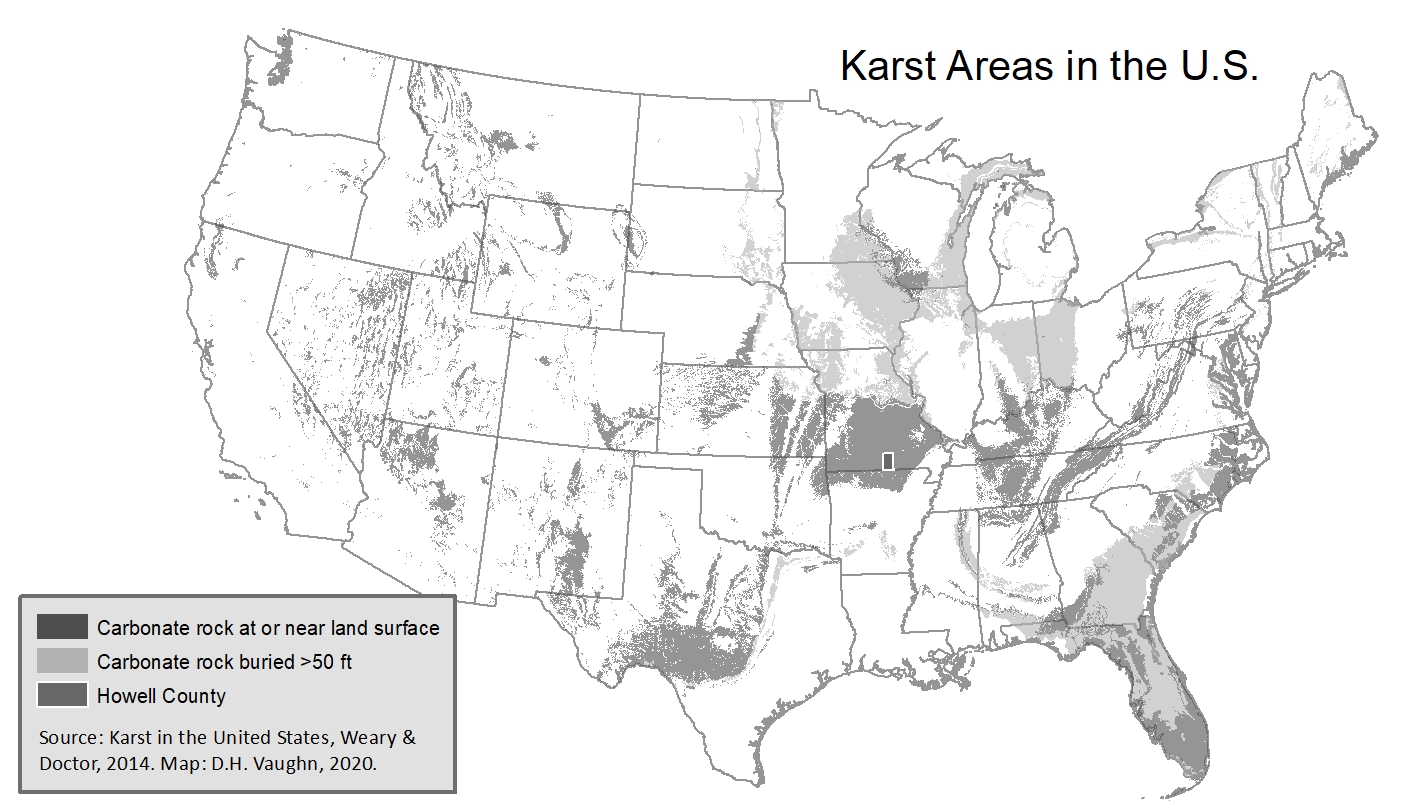

Karst topography is found in areas with soluble rock – such as limestone and dolomite – where caves, sinkholes, and springs form. Also found in karst areas are features such as sink basins, natural bridges, resurgences, and losing streams.

The word karst originated in Eastern Europe, and karst regions can be found worldwide.

The Ozarks - a major karst area in the U.S.

Learning to live on karst

Karst topography dominated the Ozarks long before humans arrived, and our ways of building on the land don’t work the same here as in other areas. In places with deep topsoil, rainwater is filtered nicely as it trickles through, making clean groundwater. But here, the thin soil filters little and the rocks beneath it do practically nothing, leaving our underground water at risk of being polluted.

Many Ozark residents - both city and rural - drink groundwater. Household wells are vulnerable, and even deep city wells have at times been infiltrated by surface water and any pollution it might carry with it.

We’ve learned a few hard-knocks lessons about what NOT to do in karst areas. In the 1960s, the city of West Plains built a sewage lagoon in a losing stream valley, but in 1978 the bottom collapsed, polluting groundwater for miles around and sickening hundreds of people. Now, most Ozark towns use wastewater treatment plants rather than sewage lagoons. In rural areas, some people are fencing livestock out of losing streams, and we’ve learned to install septic tanks in places where they won’t pollute wells for the houses they’re serving. And in cities, we've discovered that sink basins are good places for parks but they do not make good subdivisions because the houses will flood.

The better we understand karst and groundwater, the more likely we are to build things above ground that are not likely to be damaged by flooding or the ground sinking, and the more likely we are to keep our groundwater clean and safe to drink, and to be a pleasure to swim or float after it emerges in a spring.

The Ozark Resource Center's Karst Project

The Ozark Resource Center, a 501(c)3 not-for-profit in West Plains, Mo., with a mission to promote environmentally responsible practices, has a long history of projects that foster groundwater protection, dating back to the 1978 collapse of the West Plains sewage lagoon. In the 1980s, one of ORC’s projects raised awareness about pollution from septic tanks and promoted alternatives. In the late 1990s, ORC gave school presentations about Ozark karst topography and developed a map of karst features in south central Missouri. ORC has produced two documentaries that further karst education: “Karst in the Ozarks,” (2010, 18 minutes) and “Karst in Perry County,” (2020, 18 minutes), the latter of which has been shown on PBS and won two film festival awards. Both videos were produced in cooperation with Somewhereinthewoods Productions.

Director of the Ozarks Resource Center's Karst Project is award-winning journalist Denise Henderson Vaughn, who specializes in writing about the Ozarks’ forests and waters. Her stories about caves, springs, and groundwater pollution have appeared in the West Plains Daily Quill, St. Louis Post Dispatch, and Missouri Conservationist.

Denise has given numerous classroom presentations about karst, has created educational maps showing Ozark karst features, and directed the two above-mentioned documentaries. Her in-depth groundwater series that appeared in The Quill in 1998 was republished for use by Earth science teachers, and in 2003 she edited “Living on Karst, a Reference Guide for Ozark Landowners.”

In March 2022 the Missouri Speleological Survey, a statewide cave-mapping organization, presented Denise with a certificate of appreciation that recognizes her work to educate about and protect caves. She holds a master’s degree in journalism and conservation biology from the University of Missouri.